When work by Cozic started to be shown at the end of the 1960’s, Molinari was still at the peak of his glory. He had just returned from the 34th Biennale in Venice, where he represented Canada with his friend Ulysse Comtois and where his paintings from 1964-1968 earned him an important award from the David F. Bright Foundation. The holder of a major grant from the Guggenheim Foundation, Molinari had since 1962 regularly had solo exhibitions in New York City and his painting Mutation Vert-Rouge occupied pride of place in the catalogue of the prestigious exhibition The Responsive Eye held in 1965 at the Museum of Modern Art. And this is without counting the innumerable top quality events in which he participated or the awards of various sorts which he received. And he had just reached thirty-five years of age…

Molinari attracted such glory primarily due to his radical points of view. Since the autumn of 1963 he had, in fact, produced almost exclusively chromatic proposals using wide vertical bands of even widths, without showing any sign of a lessening of his passion for painting. Much to the contrary. It was the first time that he had worked on such an extensive series of paintings, even though its radicalism reminds the viewer of his black and white paintings of 1956, exhibited at L’Actuelle gallery, which “anticipated by almost ten years the minimal art of the New York School” as the great art historian Bernard Teyssèdre wrote with his usual discernement. At first glance, then, nothing predisposed the artist to considering favourably the mysterious works of a young, controversial duo of artists who may at times have given the impression of mocking the “great art” of

painting.

However, one should not forget that Moli was also the creator of small canvasses painted “in the dark” at the beginning of the 1950’s, much to the distress of the automatists. Moli remembered that he was frequently accused of being a Dadaist and that no effort was made to understand his production which instead was simply scorned. It was therefore not entirely surprising that he showed an early interest in Cozic’s fabric-based work, already unusual in the field of art, as well as in its subject matter. The couple recalls today the welcoming attitude of the artist to their work: “He attended all of our openings, where he shared with us constructive impressions and interpretations. He was the first to comment on our objects otherwise than merely stating “How cute!” His opinions were influential and greatly facilitated our integration into the Quebec art scene.”

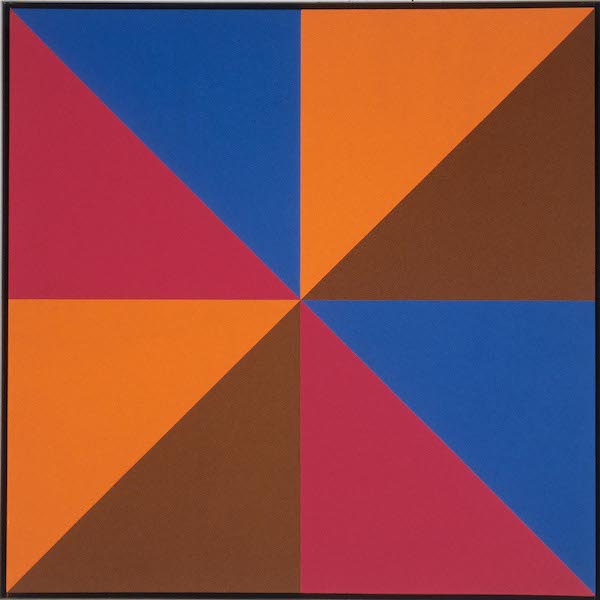

It was Moli’s intuition that, behind a façade viewed by most as playful trifles, Cozic’s artistic works often mirrored his own, through the importance paid to structure, to colour, to geometry, to the notion of series, to the time necessary to fully perceive a work of art, to viewer participation, etc. All mutatis mutandis, of course. From this perspective, the Surfacentres series, shown at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal when it was located at Cité du Havre, is particularly explicit, with all of the transgressions which fabric-based surfaces could impose on geometry. And vice versa. Our enthusiasm for these seminal works dates back to the very start of the Foundation, when the idea was formed of showing them opposite a Molinari in transition between vertical bands and the Quantificateurs series. A new Molinari, more outwardly convivial, whose principles appeared to be more supple, working within shorter timelines. A less affirmative Molinari—if such a thing is conceivable—exploring new spatial surfaces with diagonal shapes, all the while testing new groups of colours.

As a result, Cozic’s propositions may be seen not so much as the contestation of painting but rather as a renewal of its vocabulary and the enrichment of its possibilities, through means which have been their trademark since the outset: the recurring kitsch materials, in slightly vulgar colours, which so often offended “good taste”. There remains only to note Moli’s perspicacity in assessing the significance of Cozic. Although, at the end of the 1960’s, the “theoretician of Molinarism” was himself no longer a stranger to conflicts with “good taste”.

— Gilles Daigneault

Cozic

A few months before May 1968, two young graduates of the École des beaux‑arts in Montreal combined to create a single entity: Monique Brassard and Yvon Cozic became “Cozic”, a two-headed and four-handed creator known for its strangely-shaped and somewhat unusual works of art. Their joint career, spanning nearly fifty years, has been marked by innumerable important exhibitions, in Canada and abroad, and earned for Cozic the prestigious “Jean‑Paul Riopelle” Career Award of the Conseil des Arts et des Lettres du Québec. The Guido Molinari Foundation is pleased to show these works by Cozic in their most formalist mode and is grateful to the Graff gallery, most notably for fostering the career of this “gentle revolutionary” (as they define themselves) for our unending pleasure.

Read the exhibition flyer below:

Pictures of the opening reception: